FAMILIENLISTE / Sauropoda

Marsh, 1878

Saurischia Sauropodomorpha Sauropoda

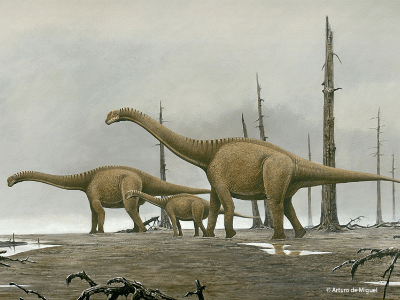

Die Familie der Sauropoda (Echsenfüßer) brachte die größten an Land lebenden Tiere hervor, die jemals auf der Erde existiert haben. Die ersten Sauropoden erschienen in der späten Trias. Im späten Jura vor etwa 150 Millionen Jahren erreichten sie ihre größte Artenvielfalt und waren weltweit verbreitet, insbesondere die Diplodocidae und die Brachiosauridae. Die bekanntesten Vertreter sind Argentinosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brachiosaurus und Diplodocus. Sie lebten bis in die späte Kreidezeit, in der es nur noch die Titanosaurier gab, bis ein Massensterben vor etwa 66 Millionen Jahren die Dinosaurier vernichtete.

Leider sind komplette Fossilienfunde von Sauropoden sehr selten. Viele Arten, vor allem die der großen Spezies, sind nur von wenig isoliertem und meist unvollständigen Knochenmaterial bekannt. Bei sehr vielen der entdeckten Exemplare fehlen Kopf, Schwanzwirbel oder Gliedmaßen. Einige Paläontologen nehmen an, dass diese Körperteile am häufigsten nach dem Tod der Tiere von Fleischfressern verzehrt wurden, bevor sie von Sediment bedeckt werden und so versteinern konnten.

Sauropoden waren pflanzenfressende Tiere (Herbivoren), besaßen in der Regel recht lange Hälse und bewegten sich quadruped (vierbeinig) fort. Viele Arten hatten besondere Zähne, die an der Basis breit waren und nach oben spitz zuliefen. Sie hatten kleine Köpfe, große Körper und die meisten Arten hatten lange Schwänze. Ihre Hinterbeine waren massiv, gerade und kräftig und endeten in einem tonnenförmigen Fuß. Der Fuß hatte auf seiner Unterseite vermutlich ein Fleischpolster, von den fünf Zehen hatten nur die drei inneren (bei einigen Arten vier) Krallen. Die Vorderbeine sind um etwa ein Viertel kürzer als die Hinterbeine. Der Oberarmknochen war länger als der Unterarm und nur der Daumen trug eine Klaue.

Zusammen mit den Pterosauriern und anderen Saurischiern wie die Vögel und andere Theropoden besaßen Sauropoden ein System von Luftsäcken in Form von Vertiefungen und Hohlräumen in den meisten ihrer Wirbelknochen. Solche Röhrenknochen sind ein charakteristisches Merkmal aller Sauropoden. Forscher rekonstruierten durch den Vergleich mit Vögeln und Krokodilen das weiche Gewebe wie Luftsäcke, Bänder und Muskeln an den Halswirbeln. Die Untersuchung zeigte, dass die Luftsäcke zusammen mit Sehnen und Muskeln eine unterstützende Funktion für die Motorik des Halses hatten. Dies würde auch bedeuten, das die Sauropoden Gewicht sparten, da sie auf besonders starke Halsmuskeln nicht angewiesen waren.

Eine Studie von Matthew Cobley, Emily Rayfield und Paul Barrett, die im Jahr 2013 veröffentlicht wurde, zeigt, dass die zum Teil beträchtlich langen Hälse nicht besonders beweglich waren. Studien am langen Hals des Strauß, dessen Hals-Struktur denen der Sauropoden sehr ähnlich ist, zeigten, dass Sauropoden keinen besonders flexiblen Hals besaßen, wie er oft in verschiedenen Medien dargestellt wird. Die Untersuchungen von Matthew Cobley und seinem Team zeigten durch verschiedene Computer-Animationen, dass aufgrund der Form der Wirbel sowie die Ansätze von Muskeln und Knorpel die Flexibilität des Halses in hohem Maße eingeschränkt war. Diese Entdeckung zeigte aber auch, dass Sauropoden um den ganzen Körper herum besseren Zugang zur Vegetation in ihren Weidegebieten hatten.

von Matthew Cobley, Emily Rayfield und Paul Barrett, die im Jahr 2013 veröffentlicht wurde, zeigt, dass die zum Teil beträchtlich langen Hälse nicht besonders beweglich waren. Studien am langen Hals des Strauß, dessen Hals-Struktur denen der Sauropoden sehr ähnlich ist, zeigten, dass Sauropoden keinen besonders flexiblen Hals besaßen, wie er oft in verschiedenen Medien dargestellt wird. Die Untersuchungen von Matthew Cobley und seinem Team zeigten durch verschiedene Computer-Animationen, dass aufgrund der Form der Wirbel sowie die Ansätze von Muskeln und Knorpel die Flexibilität des Halses in hohem Maße eingeschränkt war. Diese Entdeckung zeigte aber auch, dass Sauropoden um den ganzen Körper herum besseren Zugang zur Vegetation in ihren Weidegebieten hatten.

Sauropodomorpha

Sauropodomorpha

![]() Sauropoda

Sauropoda

. Amanzia

. Amygdalodon

. Archaeodontosaurus

. Atlasaurus

. Bagualia

. Barapasaurus

. Bellusaurus

. Cetiosauriscus

. Chinshakiangosaurus

. Chondrosteosaurus

. Daanosaurus

. Datousaurus

. Ferganasaurus

. Galveosaurus

. Isanosaurus

. Janenschia

. Jiutaisaurus

. Klamelisaurus

. Kotasaurus

. Liubangosaurus

. Lourinhasaurus

. Mongolosaurus

. Nebulasaurus

. Ohmdenosaurus

. Patagosaurus

. Perijasaurus

. Pulanesaura

. Qinlingosaurus

. Rhoetosaurus

. Shunosaurus

. Spinophorosaurus

. Tazoudasaurus

. Tendaguria

. Volkheimeria

. Vulcanodon

. Xianshanosaurus

. Yuanmousaurus

-![]() Lessemsauridae (Apaldetti, Martínez, Cerda, Pol, Alcober, 2018)

Lessemsauridae (Apaldetti, Martínez, Cerda, Pol, Alcober, 2018)

Die Klade wurde als die Gruppe definiert, aus allen Sauropoda, die aus dem letzten gemeinsamen Vorfahren von Lessemsaurus sauropoides und Antetonitrus ingenipes und all seinen Nachkommen besteht. Je nach Definition sind die Lessemsauridae die grundlegendste Gruppe oder die Schwestergruppe der Sauropoda

-. Antetonitrus

-. Ingentia

-. Ledumahadi

-. Lessemsaurus (Typ)

--![]() Turiasauria (Royo-Torres, Cobos, Alcalá, 2006)

Turiasauria (Royo-Torres, Cobos, Alcalá, 2006)

Die Klade wurde als die Gruppe definiert, bestehend aus allen Sauropoda, die enger mit Turiasaurus riodevensis als mit Saltasaurus loricatus verwandt sind.

--. Losillasaurus

--. Mierasaurus

--. Narindasaurus

--. Turiasaurus (Typ)

--. Zby

© Uwe Jelting

© Kabacchi

© Arturo de Miguel

© Raul Lunia

Weitere Informationen

Almost all known sauropod necks are incomplete and distorted / Michael P. Taylor, 2022 / PeerJ 10:e12810 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12810 /

/ Michael P. Taylor, 2022 / PeerJ 10:e12810 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.12810 / PDF

PDF

Anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Tazoudasaurus naimi (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the late Early Jurassic of Morocco![]() / Ronan Allain, Najat Aquesbi, 2008 / Geodiversitas 30 (2): 345 - 424

/ Ronan Allain, Najat Aquesbi, 2008 / Geodiversitas 30 (2): 345 - 424

An unusual new neosauropod dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous Hastings Beds Group of East Sussex, England / Michael P. Taylor, Darren Naish, 2007 / Palaeontology 50 (6): 1547 – 1564

/ Michael P. Taylor, Darren Naish, 2007 / Palaeontology 50 (6): 1547 – 1564

A new basal eusauropod from the Middle Jurassic of Yunnan, China, and faunal compositions and transitions of Asian sauropodomorph dinosaurs / Lida Xing, Tetsuto Miyashita, Philip J. Currie, Hailu You, Zhiming Dong, 2013 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica / doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2012.0151 /

/ Lida Xing, Tetsuto Miyashita, Philip J. Currie, Hailu You, Zhiming Dong, 2013 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica / doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4202/app.2012.0151 / PDF

PDF

A New Basal Sauropod Dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Niger and the Early Evolution of Sauropoda / Kristian Remes, Francisco Ortega, Ignacio Fierro, Ulrich Joger, Ralf Kosma, José Manuel Marín Ferrer for the Project PALDES, for the Niger Project SNHM, Oumarou Amadou Ide, Abdoulaye Maga, 2009 / PLoS ONE 4(9): e6924. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006924 /

/ Kristian Remes, Francisco Ortega, Ignacio Fierro, Ulrich Joger, Ralf Kosma, José Manuel Marín Ferrer for the Project PALDES, for the Niger Project SNHM, Oumarou Amadou Ide, Abdoulaye Maga, 2009 / PLoS ONE 4(9): e6924. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0006924 / PDF

PDF

A new basal sauropod from the pre-Toarcian Jurassic of South Africa: evidence of niche-partitioning at the sauropodomorph–sauropod boundary? / Blair W. McPhee, Matthew F. Bonnan, Adam M. Yates, Johann Neveling, Jonah N. Choiniere, 2015 / Sci. Rep. 5, 13224; doi: 10.1038/srep13224 (2015) /

/ Blair W. McPhee, Matthew F. Bonnan, Adam M. Yates, Johann Neveling, Jonah N. Choiniere, 2015 / Sci. Rep. 5, 13224; doi: 10.1038/srep13224 (2015) / PDF,Ergänzendes Material:

PDF,Ergänzendes Material:  PDF

PDF

A new juvenile sauropod specimen from the Middle Jurassic Dongdaqiao Formation of East Tibet / Xianyin An, Xing Xu, Fenglu Han, Corwin Sullivan, Qiyu Wang, Yong Li, Dongbing Wang, Baodi Wang, Jinfeng Hu, 2023 / PeerJ 11:e14982 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14982 /

/ Xianyin An, Xing Xu, Fenglu Han, Corwin Sullivan, Qiyu Wang, Yong Li, Dongbing Wang, Baodi Wang, Jinfeng Hu, 2023 / PeerJ 11:e14982 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.14982 / PDF

PDF

A new method to calculate limb phase from trackways reveals gaits of sauropod dinosaurs / Jens N. Lallensack, Peter L. Falkingham / Current Biology 32, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.012

/ Jens N. Lallensack, Peter L. Falkingham / Current Biology 32, 1–6, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.02.012

A new Middle Jurassic sauropod subfamily (Klamelisaurinae subfam. nov.) from Xinjiang Autonomous Region, China / Xijing Zhao, 1993 / Vertebrata PalAsiatica, Volume 31, No. 2, April, 1993, pp. 132-138

/ Xijing Zhao, 1993 / Vertebrata PalAsiatica, Volume 31, No. 2, April, 1993, pp. 132-138

A Nomenclature for Vertebral Fossae in Sauropods and Other Saurischian Dinosaurs / Jeffrey A. Wilson, Michael D. D'Emic, Takehito Ikejiri, Emile M. Moacdieh, John A. Whitlock, 2011 / PLoS ONE 6(2): e17114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017114 /

/ Jeffrey A. Wilson, Michael D. D'Emic, Takehito Ikejiri, Emile M. Moacdieh, John A. Whitlock, 2011 / PLoS ONE 6(2): e17114. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017114 / PDF

PDF

A reassessment of Vulcanodon karibaensis Raath (Dinosauria:Saurischia) and the origin of the Sauropoda / Michael R. Cooper, 1984 / Palaeontogica Africana, 25, S. 203 - 231,1984

A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) / Emanuel Tschopp, Octávio Mateus, Roger B.J. Benson, 2015 / PeerJ 3:e857 https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.857 /

/ Emanuel Tschopp, Octávio Mateus, Roger B.J. Benson, 2015 / PeerJ 3:e857 https://dx.doi.org/10.7717/peerj.857 /  PDF

PDF

A turiasaurian sauropod dinosaur from the Early Cretaceous Wealden Supergroup of the United Kingdom / Philip D. Mannion, 2019 / PeerJ 7:e6348 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6348 /

/ Philip D. Mannion, 2019 / PeerJ 7:e6348 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6348 / PDF

PDF

Additional sauropod dinosaur material from the Callovian Oxford Clay Formation, Peterborough, UK: evidence for higher sauropod diversity / Femke M. Holwerda, Mark Evans, Jeff J. Liston, 2019 / PeerJ 7:e6404 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6404 /

/ Femke M. Holwerda, Mark Evans, Jeff J. Liston, 2019 / PeerJ 7:e6404 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.6404 / PDF

PDF

Burly Gaits: Centers of Mass, Stability, and the Trackways of sauropod Dinosaurs / Donald M. Henderson, 2006 / Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(4):907-921. 2006. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1671/0272-4634(2006)26[907:BGCOMS]2.0.CO;2

Caudal Pneumaticity and Pneumatic Hiatuses in the Sauropod Dinosaurs Giraffatitan and Apatosaurus / Mathew J. Wedel, Michael P. Taylor, 2013 / PLOS Collections, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078213 /

/ Mathew J. Wedel, Michael P. Taylor, 2013 / PLOS Collections, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078213 / PDF

PDF

Cranial anatomy of Bellusaurus sui (Dinosauria: Eusauropoda) from the Middle-Late Jurassic Shishugou Formation of northwest China and a review of sauropod cranial ontogeny / Andrew J. Moore, Jinyou Mo, James M. Clark, Xing Xu, 2018 / PeerJ 6:e4881; DOI 10.7717/peerj.4881 /

/ Andrew J. Moore, Jinyou Mo, James M. Clark, Xing Xu, 2018 / PeerJ 6:e4881; DOI 10.7717/peerj.4881 / PDF

PDF

Cranial anatomy of Shunosaurus, a basal sauropod dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of China / Sankar Chatterjee, Zhong Zheng, 2002 / Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2002, 136, 145–169

Cranial Anatomy of Shunosaurus and Camarasaurus (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) and the phylogeny of the sauropoda / Zhong Zheng, 1996 / Dissertation in Geoscience

/ Zhong Zheng, 1996 / Dissertation in Geoscience

Descendants of the Jurassic turiasaurs from Iberia found refuge in the Early Cretaceous of western USA / Rafael Royo-Torres, Paul Upchurch, James I. Kirkland, Donald D. DeBlieux, John R. Foster, Alberto Cobos, Luis Alcalá, 2017 / Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 14311 () / doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14677-2 /

/ Rafael Royo-Torres, Paul Upchurch, James I. Kirkland, Donald D. DeBlieux, John R. Foster, Alberto Cobos, Luis Alcalá, 2017 / Scientific Reports 7, Article number: 14311 () / doi:10.1038/s41598-017-14677-2 / PDF

PDF

Did large foraging migrations favor the enormous body size of giant sauropods? The case of Turiasaurus / Jordi Agusti, Luis Alcalá, Andrés Santos-Cubedo, 2024 / Spanish Journal of Palaeontology 39, 2024 /

/ Jordi Agusti, Luis Alcalá, Andrés Santos-Cubedo, 2024 / Spanish Journal of Palaeontology 39, 2024 / PDF

PDF

Diets of giants: the nutritional value of sauropod diet during the Mesozoic / Fiona L. Gill, Jürgen Hummel, A. Reza Sharifi, Alexandra P. Lee, Barry H. Lomax, 2018 / Palaeontology, 2018, pp. 1–12. doi.org/10.5061/dryad.9j92p2b /

/ Fiona L. Gill, Jürgen Hummel, A. Reza Sharifi, Alexandra P. Lee, Barry H. Lomax, 2018 / Palaeontology, 2018, pp. 1–12. doi.org/10.5061/dryad.9j92p2b / PDF

PDF

High browsing skeletal adaptations in Spinophorosaurus reveal an evolutionary innovation in sauropod dinosaurs / D. Vidal, P. Mocho, A. Aberasturi, J. L. Sanz, F. Ortega, 2020 / Scientific Reports, Volume 10, Article number: 6638

/ D. Vidal, P. Mocho, A. Aberasturi, J. L. Sanz, F. Ortega, 2020 / Scientific Reports, Volume 10, Article number: 6638 PDF

PDF

How far might plant-eating dinosaurs have moved seeds? / George L. W. Perry, 2021 / Biology Letters, 17:20200689.

http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0689

/ George L. W. Perry, 2021 / Biology Letters, 17:20200689.

http://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2020.0689

Inter-Vertebral Flexibility of the Ostrich Neck: Implications for Estimating Sauropod Neck Flexibility / Matthew J. Cobley, Emily J. Rayfield, Paul M. Barrett, 2013 / PLoS ONE, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072187 /

/ Matthew J. Cobley, Emily J. Rayfield, Paul M. Barrett, 2013 / PLoS ONE, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072187 / PDF

PDF

Late Cretaceous sauropod tooth morphotypes may provide supporting evidence for faunal connections between North Africa and Southern Europe / Femke M. Holwerda, Verónica Díez Díaz, Alejandro Blanco, Roel Montie, Jelle W.F. Reumer, 2018 / PeerJ 6:e5925 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5925 /

/ Femke M. Holwerda, Verónica Díez Díaz, Alejandro Blanco, Roel Montie, Jelle W.F. Reumer, 2018 / PeerJ 6:e5925 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5925 /  PDF

PDF

Multibody analysis and soft tissue strength refute supersonic dinosaur tail / Simone Conti, Emanuel Tschopp, Octávio Mateus, Andrea Zanoni, Pierangelo Masarati, Giuseppe Sala, 2022 / Scientific Reports volume 12, Article number: 19245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21633-2/

/ Simone Conti, Emanuel Tschopp, Octávio Mateus, Andrea Zanoni, Pierangelo Masarati, Giuseppe Sala, 2022 / Scientific Reports volume 12, Article number: 19245. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-21633-2/ PDF

PDF

New anatomical information on Rhoetosaurus brownei Longman, 1926, a gravisaurian sauropodomorph dinosaur from the Middle Jurassic of Queensland, Australia![]() /Jay P. Nair, Steven W. Salisbury, 2012 / Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Volume 32, Issue 2, 2012

/Jay P. Nair, Steven W. Salisbury, 2012 / Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Volume 32, Issue 2, 2012

New information on Lessemsaurus sauropoides (Dinosauria: Sauropodomorpha) from the Upper Triassic of Argentina / Diego Pol, Jaime E. Powell, 2007 / Special Papers in Palaeontology 77, 2007, pp. 223–243

Novel insight into the origin of the growth dynamics of sauropod dinosaurs / Ignacio Alejandro Cerda, Anusuya Chinsamy, Diego Pol, Cecilia Apaldetti, Alejandro Otero, Jaime Eduardo Powell, Ricardo Nestor Martinez, 2017 / PLoS ONE 12(6): e0179707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179707 /

/ Ignacio Alejandro Cerda, Anusuya Chinsamy, Diego Pol, Cecilia Apaldetti, Alejandro Otero, Jaime Eduardo Powell, Ricardo Nestor Martinez, 2017 / PLoS ONE 12(6): e0179707. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0179707 / PDF

PDF

On remains of the Sauropods from Kelamaili region, Junggar Basin, Xinjiang, China / Z. M. Dong, 1990 / Vertebrata PalAsiatica 28, Nr. 1, pp 43-58

/ Z. M. Dong, 1990 / Vertebrata PalAsiatica 28, Nr. 1, pp 43-58

On the Vertebrata of the Dakota Epoch of Colorado / Edward D. Cope, 1878 / Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 17: 233–247 /

/ Edward D. Cope, 1878 / Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 17: 233–247 /  PDF

PDF

Origin and evolution of turiasaur dinosaurs set by means of a new ‘rosetta’ specimen from Spain / Rafael Royo-Torres, Alberto Cobos, Pedro Mocho, Luis Alcalá, 2020 / Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa091, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa091 /

/ Rafael Royo-Torres, Alberto Cobos, Pedro Mocho, Luis Alcalá, 2020 / Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, zlaa091, https://doi.org/10.1093/zoolinnean/zlaa091 / PDF

PDF

Osteological revision of the holotype of the Middle Jurassic sauropod dinosaur Patagosaurus fariasi Bonaparte, 1979 (Sauropoda: Cetiosauridae)  / Femke M. Holwerda, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, Diego Pol, 2021 / Geodiversitas 43 (16): 575-643. DOI: 10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a16

/ Femke M. Holwerda, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, Diego Pol, 2021 / Geodiversitas 43 (16): 575-643. DOI: 10.5252/geodiversitas2021v43a16

Sauropod diversity in the Upper Cretaceous Nemegt Formation of Mongolia - a possible new specimen of Nemegtosaurus / Alexander O. Averianov, Alexey V. Lopatin, 2019 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64 (2), 2019: 313-321 doi:https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00596.2019 /

/ Alexander O. Averianov, Alexey V. Lopatin, 2019 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 64 (2), 2019: 313-321 doi:https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00596.2019 / PDF

PDF

The Braincase of the Basal Sauropod Dinosaur Spinophorosaurus and 3D Reconstructions of the Cranial Endocast and Inner Ear / Fabien Knoll, Lawrence M. Witmer, Francisco Ortega, Ryan C. Ridgely, Daniela Schwarz-Wings, 2012 / PLOS ONE 7(1): e30060. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030060 /

/ Fabien Knoll, Lawrence M. Witmer, Francisco Ortega, Ryan C. Ridgely, Daniela Schwarz-Wings, 2012 / PLOS ONE 7(1): e30060. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030060 /  PDF

PDF

The complete anatomy and phylogenetic relationships of Antetonitrus ingenipes (Sauropodiformes, Dinosauria): implications for the origins of Sauropoda / Blair W. McPhee, Adam M. Yates, Jonah M. Choiniere, Fernando Abdala, 2014 / Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 171, 151–205

/ Blair W. McPhee, Adam M. Yates, Jonah M. Choiniere, Fernando Abdala, 2014 / Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 2014, 171, 151–205

The earliest known sauropod dinosaur and the first steps towards sauropod locomotion / Adam M. Yates, James W. Kitching, 2003 / Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, 2003 Aug 22; 270(1525): 1753–1758

The Effect of Intervertebral Cartilage on Neutral Posture and Range of Motion in the Necks of Sauropod Dinosaurs / Michael P. Taylor, Mathew J. Wedel, 2013 / PLoS ONE 8(10): e78214. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078214 /

/ Michael P. Taylor, Mathew J. Wedel, 2013 / PLoS ONE 8(10): e78214. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0078214 / PDF

PDF

Teeth of embryonic or hatchling sauropods from the Berriasian (Early Cretaceous) of Cherves-de-Cognac, France / Paul M. Barrett, Joane Pouech, Jean-Michel Mazin, Fiona M. Jones, 2016 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (3), 2016: 591-596 /

/ Paul M. Barrett, Joane Pouech, Jean-Michel Mazin, Fiona M. Jones, 2016 / Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (3), 2016: 591-596 / PDF

PDF

The variability of inner ear orientation in saurischian dinosaurs: testing the use of semicircular canals as a reference system for comparative anatomy / Jesus Marugan-Lob, Luis M. Chiappe, Andrew A. Farke, 2013 / PeerJ 1:e124 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.124 /

/ Jesus Marugan-Lob, Luis M. Chiappe, Andrew A. Farke, 2013 / PeerJ 1:e124 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.124 / PDF

PDF

Torsion and Bending in the Neck and Tail of Sauropod Dinosaurs and the Function of Cervical Ribs: Insights from Functional Morphology and Biomechanics / Holger Preuschoft, Nicole Klein, 2013 / PLoS ONE 8(10): e78574. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078574 /

/ Holger Preuschoft, Nicole Klein, 2013 / PLoS ONE 8(10): e78574. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0078574 / PDF

PDF

Using Dental Enamel Wrinkling to Define Sauropod Tooth Morphotypes from the Cañadón Asfalto Formation, Patagonia, Argentina / Femke M. Holwerda, Diego Pol, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, 2015 /

PLoS ONE 10(2): e0118100. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.011810 /

/ Femke M. Holwerda, Diego Pol, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, 2015 /

PLoS ONE 10(2): e0118100. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.011810 / PDF

PDF

Why is vertebral pneumaticity in sauropod dinosaurs so variable? / Mike Taylor, Mathew Wedel, 2021 / Qeios. doi:10.32388/1G6J3Q /

/ Mike Taylor, Mathew Wedel, 2021 / Qeios. doi:10.32388/1G6J3Q / PDF

PDF

Why sauropods had long necks; and why giraffes have short necks / Michael P. Taylor, Mathew J. Wedel, 2013 / PeerJ 1:e36; DOI 10.7717/peerj.36 /

/ Michael P. Taylor, Mathew J. Wedel, 2013 / PeerJ 1:e36; DOI 10.7717/peerj.36 / PDF

PDF

Zby atlanticus, a new turiasaurian sauropod (Dinosauria, Eusauropoda) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal / Octávio Mateus, Philip D. Mannion, Paul Upchurch, 2014 / Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (3): 618, doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.822875

/ Octávio Mateus, Philip D. Mannion, Paul Upchurch, 2014 / Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 34 (3): 618, doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.822875

- - - - -

Bildlizenzen

Skelett des Giraffatitan © Uwe Jelting:

Creative Commons 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Creative Commons 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Skelett des Mamenchisaurus © Kabacchi:

Creative Commons 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

Creative Commons 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)

- - - - -

Grafiken und Illustrationen von Raul Lunia

Grafiken und Illustrationen von Arturo de Miguel